Inventory crisis shows little sign of improving

While mortgage holders may soon find reprieve from punishing interest rates, Australia’s renters are facing a worsening crisis fuelled by a long-running undersupply of new housing and surging migration.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is tipped to deliver up to four rate cuts in 2025, with the cash rate expected to fall to 3% by year’s end. This would ease the repayment burden on many mortgage holders, who, according to Westpac, have seen average minimum repayments rise 42% – or about $754 – over the two years to January 2024, compared with just an 8.5% rise in incomes.

However, the outlook is far less optimistic for renters. Even though rental payments have risen a smaller 40% over the same period, renters face escalating costs without the prospect of imminent relief. According to CBA data, housing costs for tenants have continued to climb due to persistent supply constraints and unrelenting population growth.

Data released by the Urban Development Institute of Australia (UDIA) paints a sobering picture of the supply side. New housing production remains significantly below historical norms, despite some year-on-year recovery. In 2024, just 42,700 greenfield lots were released across the capital cities – a 15% rise on 2023, yet still 20% below the long-run average and 46% below the 2021 peak.

Completions of detached houses in infill and greenfield sites remained subdued, with approximately 79,000 built nationally in 2024, a figure the UDIA notes is inadequate given the country’s surging demand.

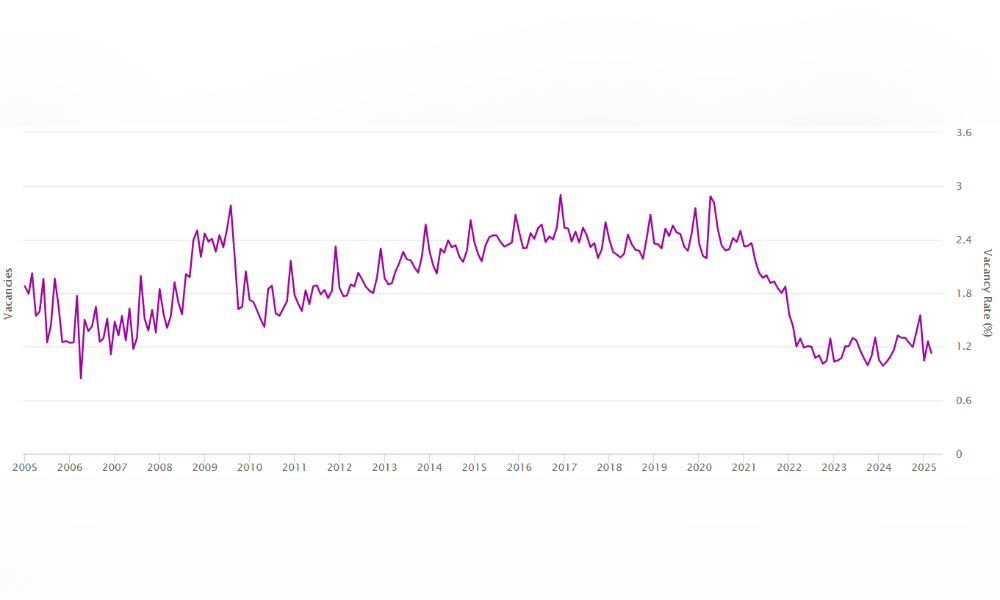

This imbalance is being acutely felt in the rental market. As net overseas migration continues at historically high levels, vacancy rates have stayed critically low. ABS data suggests the first quarter of 2025 saw another uptick in long-term arrivals, further stretching a housing stock already under pressure.

Graph title: Resident vacancy rates plummet

Credit: SQM Research

Alan Kohler summed up the core issue to ABC last month: “The root of the housing crisis is that dwelling approvals have been declining for 10 years and immigration has been rising for 20 years, with the result that too many people are now chasing not enough houses.”

To cope, many renters are turning to shared housing arrangements. Nationally, average household sizes have ticked upward, reversing pandemic-era trends. But this is a stopgap, not a solution.

Read more: Government has ‘entrenched inequality’ in Australian rental market

Despite mounting political pressure, the UDIA warns that a supply-led recovery remains some way off. In fact, the report projects subdued greenfield activity in 2025. With fewer large-scale land estates coming online and construction costs still high, developers are struggling to deliver housing at price points accessible to ordinary Australians.

Moreover, while the build-to-rent (BTR) sector has seen some growth – with completions rising fivefold in 2024 – it remains too small to fill the gap left by declining multi-unit apartment construction.

Ultimately, tenants have fewer levers to pull than mortgage holders. Interest rate cuts offer no direct benefit to renters. Without a structural increase in housing supply – particularly affordable and purpose-built rental housing – the squeeze is likely to tighten.

As the UDIA bluntly puts it: “The main issue facing the national greenfield market in 2025 will be finding ways to deliver necessary products at prices that align with the customers' financial capacities.”

Without a national plan to better match migration with housing construction, renters may find there is no way out.