Experts say get ready for lower mortgage payments

The Bank of England is preparing to reduce interest rates again next week, in what is shaping up to be one of its most closely watched decisions since the pause in monetary tightening last September.

Rising concern over global economic fragmentation, spurred by President Donald Trump’s newly announced trade tariffs, has added urgency to the central bank’s deliberations. Governor Andrew Bailey, speaking recently in Washington, stressed the need for policymakers to be “realistic” about the damage that protectionism could inflict on the UK’s already fragile economic outlook. “Trade does support growth,” he said. “Fragmenting the global economy would be bad for growth.”

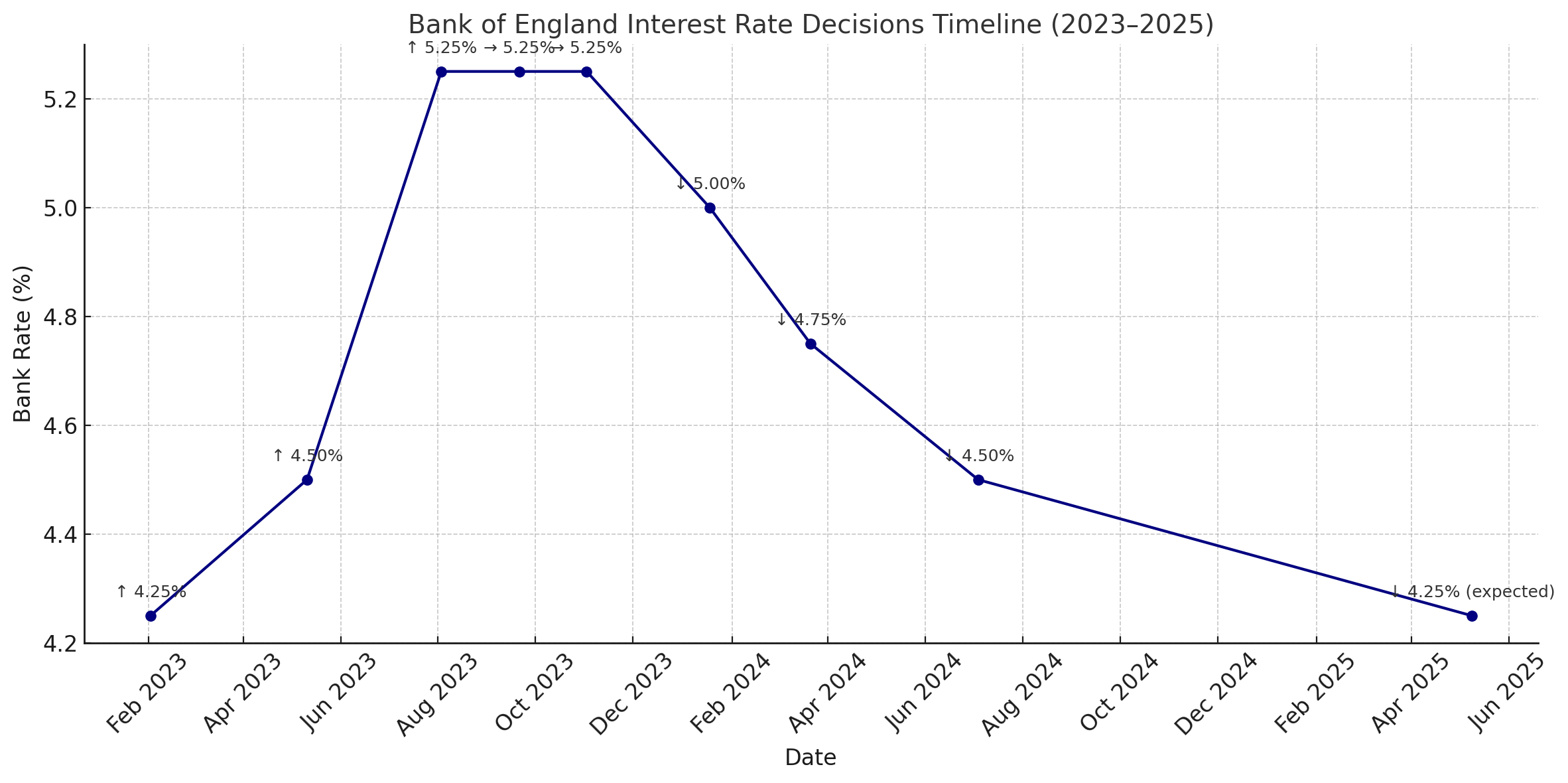

Bailey’s remarks come ahead of the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting on Thursday, where a cut of 0.25 percentage points — from 4.5% to 4.25% — is widely expected. This would mark the fourth rate reduction since last August. However, economists now increasingly believe the Bank will continue easing policy in the coming months, potentially accelerating the pace of cuts if the global economic environment deteriorates further.

Tariffs, Tensions and Tumult

President Trump’s “reciprocal” tariff plan, unveiled on April 2 — dubbed “Liberation Day” by his administration — includes a flat 10% duty on all UK imports, along with a much steeper 145% levy on Chinese goods and targeted taxes on cars and metals. While implementation of many of these measures has been delayed until July, financial markets have already felt the tremors. In recent weeks, the pound has risen sharply against the dollar, and oil prices have fallen, providing a small buffer to domestic inflation. But the overarching concern for British policymakers is the chilling effect of uncertainty. UBS and Barclays have both warned that if Trump’s tariffs begin to weigh more heavily on trade flows, the Bank of England may need to cut rates more frequently — potentially at every MPC meeting through to the end of the year.

Such caution is echoed by Clare Lombardelli, a deputy governor, who recently noted that tariffs “have the potential to depress UK growth.” External committee member Megan Greene went further, suggesting the tariffs could exert downward pressure on prices rather than raise them, describing the potential impact as “disinflationary.”

Data Driving the Dovish Turn

Recent economic indicators support a looser monetary stance. Inflation in March fell to 2.6%, below expectations, with core inflation and services inflation also easing. Labour market data pointed to softening conditions: job vacancies declined again, and the ratio of unemployed persons to available jobs climbed to two — a figure not seen since before the pandemic. Yet, the MPC remains split. While the majority appears inclined to move cautiously with successive quarter-point reductions, a bloc of more dovish members — including Catherine Mann and Swati Dhingra — have pushed for deeper cuts, with Mann having supported a 0.5 percentage point cut at the February meeting. Analysts at Morgan Stanley now anticipate rates could fall to 3.25% by November, while other forecasters suggest a terminal rate of 3–3.5% by mid-2026.

The divergence of views reflects the complex balancing act facing policymakers. On the one hand, inflation is easing, and growth prospects are weak — particularly given external shocks. On the other hand, wage growth remains elevated, and the economy showed surprising strength earlier this year, with February GDP growth coming in at 0.5%.

Politics at the Periphery

While the Bank operates independently, political figures will be paying close attention. Chancellor Rachel Reeves, keen to avoid the pitfalls of her predecessors, has made fiscal restraint a cornerstone of her economic platform. According to Treasury sources, her decision not to ramp up borrowing in the Spring Statement has given the Bank of England “greater room” to adjust policy. Still, the spectre of Trump looms large. Trump’s policies have sharply curtailed the Federal Reserve’s capacity to lower rates, due to the inflationary spillover from tariffs. British officials are eager to avoid a similar bind. Reeves has hinted at a willingness to negotiate on reducing car import tariffs in future UK–US trade talks — a potential avenue for softening the blow.

Thursday’s rate decision will be followed by a press conference where Bailey is likely to field questions not only about the path of interest rates but also about central bank independence, a hot-button issue following Trump’s recent criticism of US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

The Limits of Monetary Easing

While lower rates may bring relief to mortgage-holders and consumer borrowers, they are no cure-all. The UK economy remains beset by long-term structural weaknesses — sluggish productivity, constrained investment, and anaemic real wage growth — that monetary policy alone cannot fix.

The Bank of England’s challenge now is to maintain credibility while responding flexibly to events beyond its control. As one senior economist put it: “Rate cuts may help, but they are a plaster, not a cure.”